THE TRICKSTER

a memoir

by Eva Margueriette

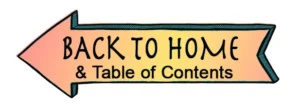

The Vegetable Garden, by Eva Margueriette, 1994, WC, 11×14, Margie Burton collection.

The Vegetable Garden, by Eva Margueriette, 1994, WC, 11×14, Margie Burton collection.

5. The Victory Garden

The proper environmental conditions must exist for germination and growth. –Mother Earth News

IN THE SPRING OF 1975, hyperinflation, the declining dollar, and Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan bombarded the nightly news. In the wake of the oil crisis, Roy Masters, a Jewish hypnotist from England, spouting Christian doctrine, prophesizing socioeconomic collapse and global famine exhorted his radio audience to become self-sustaining.

In Terry’s tenth year, anxious about my children’s future, I tuned to his talk show seeking guidance. Even with my powerful hearing aids, I depended on lip reading for clarification, but my residual hearing fell in the low tones and Mr. Masters had a powerful, low-toned voice. He enhanced his delivery with theatrical pauses and passionate tirades like Burt Lancaster in Elmer Gantry which drew me in and kept me listening with my eyes closed, concentrating, my ear pressed against the speaker. Because his tirades magnified my guilt and motivated me to surrender cigarettes and diet pills, I gave credited him for saving me from addiction.

The master had all the answers. He also promised me salvation and the enlightenment I craved if I practiced his self-hypnosis meditation, ordered his book, overcame resentment toward my husband, and donated ten dollars a month to keep his show on the air. An expert on the Bible, which also impressed me, he often quoted Saint Paul, Wives submit unto your own husband…the spiritual leader of the family.

Reluctant to broadcast my voice over Los Angeles County, but frustrated by Stuart’s refusal to be the spiritual leader of the family to whom I could submit, I called Roy Masters.

“Hello,” he said. “What’s your question?”

I clenched the receiver in my clammy hand. “It’s about my husband, he comes home drunk every night. I’m afraid it’s killing him.”

“Do you have children?”

“Yes, and his drinking is robbing them of a father they can respect.”

“Do you resent your husband?”

“Yes. But I don’t want to. I love him.”

“You know, it’s a sin to resent your husband.”

That’s all I heard. His voice faded as he moved to the next caller. The dial tone moaned.

Weeks later, like an abused woman returning to her abuser, I tuned into Master’s talk show again. A male caller praised Mother Earth News, a magazine for hippies and off-the-grid survivalists preparing for the end times. The two men agreed everyone must plant a vegetable garden, stockpile pork and beans, water, fifty-pound bags of wheat, guns, and ammunition.

I immediately subscribed to the magazine and devoured articles on how to grow and store food, grind wheat, raise chickens, slaughter pigs, sew quilts, make beeswax candles, and lye soap like Mammaw made in the shed. My grandmother also had a Victory Garden during World War II. Inspired by her example and the guru’s dire warnings, I decided to plant vegetables to save my family from the looming famine.

On a Saturday morning, I bought carrot, beet, cabbage, green bean, and beefsteak tomato seeds at the nursery. Unaware of the back-to-the-land movement in the mid-seventies, I assumed everyone in the crowd was planting Victory Gardens in their backyard to survive the apocalypse.

Shaded by thirteen eucalyptus trees, the kids and I pushed shovels into the lawn, ripping chunks of Bermuda grass and roots, imagining our harvest piled on the kitchen table.

Stuart stopped changing the TV channel from golf to baseball to basketball and appeared in the doorway in his undershirt and boxer shorts, smoking a cigarette. He shook his head grinning as if enjoying a private joke. Perhaps he was laughing at the futility of our efforts, but we continued to tug at rocks, turn the soil, and plow furrows in our plot of sacred ground.

Terry poked at the minuscule cabbage seeds in his hand. “Are they magic?”

“Oh, yes! Inside their seed coats an embryo containing leaves and roots await the proper conditions for germination and growth before popping out,” I said, sounding like an over-enthusiastic botany teacher. “And with the right amount of oxygen, water, and lots of light, we’ll soon be making coleslaw.”

Melissa opened a packet. “Will these tiny green seeds grow big like Jack’s Beanstalk?

“That would be magic! Let’s plant them and see.” The children, their faces bent close to the ground like, The Gleaners, Jean-Francois Millet’s masterpiece. When all the magic seeds were sown, we watered them lightly careful not to disturb the miracle unfolding.

![]()

6. Mysteries

FASCINATED WITH ILLUSION, TERRY hid under his bed covers, flashlight in hand, memorizing card and coin tricks illustrated in Secrets of Magic. Weeks before his tenth birthday, he asked Santa for a beginner’s magic set.

In Southern California’s eighty-degree heat, Christmas came anyway with its unfulfilled expectations, credit card debt, homemade fudge, and weight gain. Melissa got her wished-for doll and Terry, a black cardboard box filled with linking rings, a restoring rope, and Cups and Balls, a classic illusion known as legerdemain (lightness of hand) depicted in Bosch’s painting, The Conjurer,

After days of practice waving his magic wand, he pulled a stuffed rabbit out of a black top hat. “Wow, Terry!” Melissa said. “How’d you do that?” Truly, we wondered. We cheered. The magician bowed.

Next, he vanished a silver quarter in his hand. Retrieving the coin behind my ear, he accidentally touched one of my hearing aids causing a high-pitched squeal called feedback before manifesting the coin in his long-fingered hand.

“He has the hands of a concert pianist,” my mother said at his birth. I hoped my son would inherit her love of classical music as I had at the age of ten when I got hearing aids and heard the violin’s high squeaky notes for the first time. Listening to her Fitz Kreisler records, I’d begged for a violin for Christmas. Because my mother told me I could do anything I put my mind to, my love of music led to taking violin lessons and the joy of singing in children’s choirs.

Motivated by Roy Master’s continued warnings of the coming famine, I pushed aside my disappointment about the failed vegetable garden and bought three Rhode Island Red chicks guaranteed to lay brown eggs.

Exhibiting his mastery of Cups and Balls, Terry put a ball beneath one of three cups and shuffled them on his TV tray. Two turned up empty. Melissa pointed to the last cup. “The ball’s under there!”

Beaming, he lifted the rim and out popped a live yellow chick.

Soon the chicks got too big to fit under the magic cup. We built them a one-of-a-kind coop with two-by-fours and chicken wire in the backyard, discarding the WARNING tag, we secured the hexagonal wire mesh to the frame with the staple gun I’d used to fabricate the Saint George fifty-by-sixty-inch canvas.

In the two years since Terry received his beginner set, his collection had grown to over twenty professional tricks bought at the Temple City Magic Shop where secrets were sold contingent on adherence to the magician’s code. His latest treasure, a blue-lacquered conjuring box painted with pentagrams and new moons he’d bought from a fellow Mystic’s Club member, included directions for making a dove disappear in its mysterious black velvet interior. At bedtime, Terry asked to buy a white dove and a dwarf rabbit. “I want to transform one into another.”

“Of course,” I said, turning out the light. “We’ll build more cages.”

“Daddy,” Melissa screamed. “Daddy, come quick!” In the middle of the night, Melissa awakened by screeching outside her window. One hen had vanished from the coop. The other two, wings flapping, hopped in circles like marionettes beneath the waning moon. Stuart’s flashlight spotted two yellow-eyed, masked bandits as one wrenched a second hen through a jagged tear in the chicken wire. “I’ll get the shotgun!” Stuart said, rushing to the bedroom closet.

Waiting for the father to save our little flock, no one thought to charge out into the night and chase off the predators. Stuart returned with the loaded gun at the exact moment a raccoon yanked the last chicken out of the coop and dragged it down the wash behind the eucalyptus.

In the morning, reddish brown feathers covered the blood-soaked ground where the Victory Garden died. The frame of two-by-fours, an empty tomb.

Melissa blamed her father. I agreed until I remembered the tag I’d discarded as unimportant: WARNING! Chicken wire is not guaranteed to keep out predators.

![]()

7. The Magician

SUNLIGHT STREAMED THROUGH THE sliding glass door. The jazzy movie theme, The Sting, blasted from the cassette player. Terry stood beneath Saint George behind his gold-fringed conjuring table showing the back of his hand holding one glittering billiard ball between his long fingers. Synchronizing every move to music, he multiplied the ball into two, three, and four, and vanished them in succession until one rested between his thumb and forefinger. Since turning twelve, his long fingers made it easier to switch, ditch, and conceal objects and for months he’d stood before a mirror manipulating balls, cards, and coins.

He’d sworn the Magician’s Oath, not to perform illusions until mastered, nor reveal secrets to non-magicians and Melissa became his assistant and trusted secret keeper. Grateful to have happy, creative children in a house filled with music, I believed I’d made the right decision to quit painting and focus on my family.

We built a hutch for a dwarf bunny and a cage for two white doves with sturdy wire, high off the ground, safe from predators. The sweet sound of my son’s realized dream cooing outside the kitchen window soothed my soul.

One morning, eating store-bought eggs, Terry announced their plan to put on a performance. He and Melissa created a flyer: MAGIC SHOW, starring Terry the Magnificent. Live Doves and a Rabbit! They sold fifty-cent tickets to the neighbors for the premiere in our garage the following weekend.

Roaming the aisles at American Veteran’s Thrift Store in Azusa, we crossed wishes off Terry’s list of things needed for the show: long white gloves for Melissa, short ones for him, and a black cape found in a discarded Halloween Dracula costume.

Melissa pulled a red silk scarf out of an old purse, “Look what I’ve got, Terry!” His eyes sparkled like his levitating Zombie Ball. He wanted more and searching we found ten scarves, rich in silk and vibrant color for ten cents each.

Afraid the doves might fly out of the garage during the show, I said we had to clip their wings. “Does it hurt?” Terry said.

“No, it’s like getting a haircut.” He consented and gently splayed the dove’s wings. Trimming their primary feathers, I admired his patience even during their long rehearsals he’d demanded perfection of himself and his nine-year-old sister but he’d always been patient with her.

On the day of the show, the audience stood in the driveway. Small children crowded upfront. Cantina from Star Wars rang out as Terry the Magnificent appeared; a black cloth stretched between his hands. The Floating Zombie Ball skittered along its edge, slipped beneath the fabric, rose like a ghost, and vanished. Next, the Dancing Cane levitating in midair collapsed into a bouquet of flowers in his hand. The crowd cheered. Terry bowed.

Like a debutant, Melissa glided onstage in her long white gloves and laid a rope on the conjuring table. Terry asked a little girl to come up and cut the rope and wielding his wand, he restored the rope to wholeness. He accomplished these theatrics with such aplomb, that vulnerable to deception and tricks of the mind, believed my son had invited the mystical into the garage. The little girl stared at the rope. “How’d you do that?” The sorcerer grinned. “It’s Magic!”

“Look!” the children cried as a red scarf peeked out of the top hat. Terry feigned surprise as he pulled a rainbow of ten ten-cent, tied-together silks from his empty hat. The crowd went wild.

The applause died down. Melissa swept on stage carrying a white dove perched on a wand and stood by her brother now wearing his Dracula cape. The music softened. Beyond our cul-de-sac, green mountains faded to lavender in the evening light. The mysterious, blue-lacquered box sat on the conjuring table.

The parents hushed their children. Terry removed the collapsible sides proving the vessel of illusion empty. Replacing them, he took the dove from his sister, smoothed its clipped wing, gently laid it in the box, and closed the lid. Flourishing his wand over the entombed bird, he bellowed, “Abracadabra!”

The audience gasped. He lifted the lid and out hopped a live white rabbit.

Terry’s face glowed. The show seemed enchanted, removed from everyday life, like peeking into another dimension.

As a painter, I’d created illusions, deceiving the eye with shape and color, and like my son, experienced the love of my art and inner spirit guiding my hands.

“A great show,” a neighbor said. “You must be proud!”

Terry’s dedication to craft was rare in a boy of twelve but I denied being proud of his artistic accomplishments or my own since hearing the radio guru expound, Pride goeth before the fall and the haughty spirit before destruction! Not understanding knowing my worth was a good thing, I’d added pride to my growing list of guilty sins to be avoided or overcome,

After the magic show, Melissa and Terry performed at nursing homes and kids’ birthday parties, and, on his thirteenth birthday, he announced his desire to audition at the famous Magic Castle in Hollywood. Junior Membership was open to thirteen to nineteen-year-olds seriously interested in the art of magic. He had six months to rehearse with his sister and perfect his sleight-of-hand while keeping up with his tennis tournaments, baseball, and long-distance bike rides.

Our son’s magic, his cooing doves, loving collaboration with his sister, the joy they’d brought to children’s parties and nursing homes, and the light in their eyes fulfilled my utopian environment for my children—in our own home.

On the morning of the long-awaited audition, Melissa wore her long dress and white gloves and Terry his plaid sports jacket. He spent time in front of the mirror adjusting his bow tie and combing his hair. They packed the conjuring table, blue-lacquered box, doves, rabbit, top hat, silks, billiard balls, and five linking rings into the woody wagon. Stuart had no intention of going, but at the last minute, he offered to drive. Arriving at the Magic Castle, we hauled all the magic paraphrenia into a hallway. A man invited Terry into the audition. We all stood up. “I’m sorry, only one of you can come in.” Melissa stepped forward, holding the dove cage.

“She’s my sister,” Terry said. “My assistant.”

“Sorry, assistants aren’t allowed in auditions.”

Suddenly, Terry and Stuart disappeared. The door closed. Why had my husband been the one admitted? Melissa and I sat staring at the brocaded wallpaper in the deserted hall until the door opened an hour later and father and son reappeared. I jumped up. “What happened?”

“He didn’t make it,” Stuart said.

“What do you mean?” I tried to imagine what went on behind the closed door. Perhaps not having his assistant affected his performance or the competition tougher than anticipated. Loading the car, drizzle turned to rain. My son avoided looking at me. Tears pooled in his brown eyes. I had no wand to wave.

![]()

The Storm, WC, 22×30, (private collection) Eva Margueriette

8. The Storm

A TROPICAL STORM BARRELING up the coast from Mexico hit the valley during the Hollywood audition. Coming home, low clouds and sheets of rain shrouded the San Gabriel Mountains north of Royal Oaks School. I made lunch and refilled our coffee mugs. Terry and Melissa dragged the magic props back into the house, picked at their sandwiches, and disappeared behind shut doors.

I searched my husband’s vacant gray eyes. “What happened in the audition?

The judges told him he was very good for his age.”

I gripped my cup. “He is.”

“They asked if he wanted to come to the Magic Castle on weekends and do close-up at the tables.”

He loves close-up,” I said. “Sleight-of-hand. Coins. Cards.”

Rain beaded on the window. Stuart tapped the pack of Camels in his pocket which meant he wanted to go outside, stand in the breezeway, and smoke.

“But you said, he didn’t make it.”

“When a judge asked if he wanted to do close-up at the club, he said, no.”

“He said, no?” I hugged myself trying to keep warm.

“He said he only wanted to do stage magic.”

“I don’t understand. He loves performing sleight-of-hand and close-up.

Stuart sipped his coffee gone cold. “Terry may be a genius, but he’s an egomaniac. He just wants his own way.”

I slammed my cup on the table. “Damn it, Stuart, that’s not true!”

He lifted a cigarette out of his shirt pocket and slipped out the back door. Tears dripped on my cheeks like the rain off the eaves. It made no sense. If he failed the audition, why did they invite him to perform on weekends?

I wished my husband hadn’t sobered up just in time to drive us to Hollywood and screw everything up. Maybe Terry didn’t understand the judge’s offer. Why didn’t Stuart offer him fatherly advice? It might have made a difference. Maybe I wouldn’t have done a better job in the audition, but I wish I’d had the chance. I wanted to drive back to the Magic Castle in the storm and tell the judges it was all a terrible misunderstanding.

I wish I’d said, “Terry, you’re thirteen. You must try again. Successful people suffer rejection but keep trying until they make it, but I didn’t have those words of wisdom yet, not for him or for myself.

In our current digital universe, it’s hard to imagine 1978, living in a world without computers, twenty-four-hour access to unlimited information, and step-by-step online registration. Many years later, much too late, clicking on The Magic Castle website, I discovered the misunderstanding wasn’t all Stuart’s fault and I stopped blaming him.

The information I’d failed to get before the audition and what none of us knew those many years ago was, only members, twenty-one and older, perform stage magic. Junior Magicians, aged thirteen to twenty, who pass the audition, are invited to do close-up magic at the brunch tables on weekends.

I grieved again, knowing he did make it. The judges had offered him the dream he’d worked so hard to achieve. Junior Membership in the Magic Castle.

That afternoon, as the storm beat on our roof, Terry stored his professional magic tricks in the back of his closet. He refused to discuss what happened in the audition or why he quit his passion.

Lamenting the death of my son’s vision, I recalled snuffing out the magic in my own life when I quit painting after my first successful one-man exhibition—also misconstrued as a failure.

My son and I, much alike, thrived in the pursuit of our dreams, but on the brink of success had succumbed to the implacable agent of our own undoing. Remembering the pain in Mr. Ellington’s eyes, I understood how he too must have mourned the loss of what could have been.

In the months to come Terry refocused his creative energy on improving his tennis game, and never performed another magic trick in his life. Except one.

A group of parents came to our house to discuss concerns about kids experimenting with drugs at Terry’s junior high school. A father with a son in Terry’s class said his ninth-grade son got caught smoking pot at the high school. “The school can’t control drugs on campus, and I can’t control my son at home.”

“It’s hard,” a mother said. “When they get older.”

“Yes, he was a good kid, but now he lies to us and sneaks out at night.”

Thank God, it’s not my son, I thought. That could never happen to our family. Terry was too busy with sports to get into trouble. Wanting to help the man, I passed along the advice I’d heard Roy Masters give a father in the same predicament. “If he was my son, I’d just lock him up in his room!”

“I wish it was that simple,” the father said.

Days later, Roy Masters ranting on the radio about kids, drugs, and the deplorable state of public schools, offered his solution, the Foundation School. “It’s legal and incorporated,” he said. “You can start your own Foundation School with other like-minded parents and protect your children.” I envisioned Shangri-La, a “safe haven” where no harm could come to my children. An idealist since art school sandwiched the Beatniks and hippies in the early sixties, I’d wanted to explore such utopian experiments.

Terry complained about eighth graders smoking pot under the bleachers. He took the camera to school to get proof. The photos came back fuzzy, the evidence inconclusive, but I worried about Terry returning to junior high in the fall with kids his age smoking pot.

I tuned in Master’s program daily. Unable to listen while cooking and cleaning like most housewives, I sat with my ear glued to the speaker, eyes closed— concentrating. I didn’t always hear the caller’s question or the master’s advice, but when he harangued about pot-smoking children in public school and the saving grace of his new school, I didn’t miss a word.

“The Foundation School is all about prevention,” I told Stuart. “We have happy children and I want to keep them that way.” He hated the radio guru. I knew he would resist taking the children out of public school, but I had all summer to find a suitable location, recruit parents, and convince my husband.

![]()

9. Mayhem

IN THE COMING MONTHS, I drove Terry and Melissa to AYSO soccer practice twice a week in different locations at overlapping times and attempted to attend two Saturday morning games at once. Stuart worked nights, came home drunk, and slept until noon.

Terry also played USTA junior tennis tournaments and baseball. Trophies lined his bookshelf. He dazzled his father’s golf buddies with his innate athletic talent. “If he keeps this up, he’ll get a golf scholarship to college.”

College? I couldn’t think that far ahead, except when worried about the impending economic collapse and scarcity of food preached by Roy Masters on the radio. Motivated by Sugar Blues, a book exposing the horror of refined sugar, I canned fruit in its own juice and concocted granola with natural honey, oats, walnuts, and raisins. We ate it like milk and cookies for breakfast. Melissa and I gained weight. Terry only grew taller. Stuart only ate Sugar Frosted Flakes.

When a Master’s talk-show caller raved about dehydrated fruit storing well, I bought a secondhand dehydrator. We lugged home crates of apples and bananas and the children spread sliced bananas on trays and slid them in the food dryer. Two days later, the moist, plump fruit shrunk to a handful of dried chips we sealed in Mason jars and hid behind the canned fruit I’d stored in the back of the linen closet to avoid my husband’s sneers.

One day, a man told Roy Masters he worried about protecting his hoard of dried fruit and pork and beans when society fell apart and I imagined starving people roaming the streets trying to steal my canned peaches and pears. The caller suggested everyone buy a .45 blue-nosed Colt revolver to protect their stockpile. Guns terrified me, but Stuart liked them, and I talked him into buying the Colt 45.

Imitating the movie star in Rocky, Terry downed two raw eggs for breakfast and went on a run. I’d also been working out at my new job. Inspired by a Mother Earth News story about a woman, who like me needed money, and cleaned two physician’s homes once a week, I told a neighbor I wanted to clean houses. By coincidence, she knew a doctor’s wife looking for a housekeeper.

My experience consisted of amphetamine-driven cleaning sprees when expecting company and even with a college degree, I couldn’t turn on her deluxe vacuum cleaner. Anita, my new employer kindly taught me which buttons to push and how to clean bathrooms and dust everything—every week. Approaching the work with the same enthusiasm and attention to detail I’d given to painting, I enjoyed the same sense of accomplishment. Within a year she referred me to a doctor friend. Voila! I’d manifested my dream of cleaning two physicians’ houses.

The children started their own business cleaning sidewalks with a garden hose before school. Terry expanded to storefront windows, wielding his squeegee with the same flare he’d waved his wand. Smears vanished. Plate glass sparkled. He drew himself hanging from a skyscraper on a professional rope descent system and a stretch limousine parked on the street below with Terry’s Window Washing Service printed on the side. “I have dreams for my future,” he said.

Researching the possibility of starting my own school, the children and I drove around looking for rental space in public buildings, and to my surprise, we met several community leaders sympathetic to our quest.

I wanted my children safe but also wanted them to learn by doing at their own pace, not by rote and rigid rules. At seventeen, I discovered my interest in painting made learning exciting and easier. Joseph Campbell’s dictum, Follow your bliss, would lead Terry to find his new passion in the new school.

In August, a minister requested a written proposal for an available church classroom. Not knowing how to write one, but believing in learning by doing, I checked out a library book and copied a sample proposal. Aided by a manual typewriter and liquid whiteout, I stated our mission.

We’re founding a one-room school for children of all ages in a—run by the parents. An artist, good at creating illusions, I typed an official-looking proposal complete with a make-believe letterhead, FOUNDATION SCHOOL, and mailed copies to the minister and other prospects.

Thanks to my friend Kathy who lived in Glendora and vouched for me, the Boy Scouts agreed to rent us a spacious log cabin located in the park only six miles from our home for fifty dollars a month.

I acquired a list from Roy Master’s headquarters and invited interested parents to a meeting at our house on a night Stuart was working. Six families with fifteen children signed up. A possibility had become a reality. The only glitch—I still hadn’t convinced my husband.

Monday morning, a week before school started, Stuart was leaving for his weekly golf date with his drinking buddies. Sounding upbeat, I said, “Guess what? We got the Boy Scout building for the school!”

He looked past me as if my words made no sound. He knew we’d been looking for a place to start an alternative school in the fall. “I know you don’t like the idea, but they’ll blossom in a protected environment.” I kept talking like Br’er Rabbit pleading with the Tar Baby made of pinewood tar and turpentine who had no ears. “I don’t want our kids ending up drug addicts in public school.”

He bristled. I could see his aura turning red. My heart beat faster. He’d never hit me before, but I feared he might. “I won’t discuss it!” he snarled, storming out the front door lugging his golf bag. “And by the way, my steak better be ready when I get home.”

“I just want a better life for our children,” I cried. “Better than we had.”

Standing in the doorway, I smelled smoke. A wildfire ignited in the Angeles National Forest, fueled by Santa Ana winds was creeping down the mountainside blowing ashes in our yard. Not ideal conditions for a family barbecue.

My mother barbecued chuck steak, Texas style on Sunday nights. I was fourteen that summer she invited Stuart to dinner. We’d been going steady for six months. Darkness descending, steaks grilling over glowing briquettes, Stuart wedged next to my mother on the patio steps downing cans of almost frozen Coors, joking like old friends.

Dripping fat fed the flames leaping at the steaks. Mother jumped up. Like a fireman saving a burning house, she doused the inferno with a squirt bottle and resumed chatting with my eighteen-year-old boyfriend. Like the mother in Glass Menagerie, she seemed to crave masculine attention. Suspecting she liked him more than me, I wondered if she wished she’d had a son instead.

The fire glowed. The steaks sizzled. Sitting on the steps, side by side, smoking and downing another beer my mother said to Stuart, “You gotta’ feed the cow to get the calf.” I didn’t understand the joke or why they kept laughing.

.

The forest fire advancing down the mountainside, like my mother, I drowned the cheap chuck steaks in Chris & Pitts BBQ sauce and MSG tenderizer and later, sloshed half a can of lighter fluid on the coals, lit the fire and waited for them to burn bright and even, ready for our Texas style family feast.

We waited. Stuart was late as usual. His foursome always drank beer after golfing all day. Tired of waiting, I cooked steaks for me and the children.

We’d just finished eating when he staggered into the kitchen reeking of alcohol. “Where’s my steak?” he said, waving a lit Camel too close to my face.

“Please, not in front of the kids. Calm down.”

“Don’t tell me what to do!”

“I was waiting to see the whites of your eyes,” I said to lighten his mood.

Smoldering rage hung in the air. “So, it’s not cooked?” Stuart headed for the bathroom. I stepped out on the patio and threw his steak on the grill. Dry brush burned in the distance; hot fat dripped on the coals whipping up a firestorm attacking his steak. I turned to retrieve the squirt bottle to extinguish the flames, but discovered the sliding glass door was locked. Melissa sat on the living room carpet, crying. I knocked. She didn’t move.

Flames engulfed the steak. I grabbed the singed meat off the grill and ran to the back door—also locked. I raced back to the patio. Terry peeked out between the curtains, looking over his shoulder, he opened the door, a crack. “Dads mad. He locked you out.” Stuart appeared, his arms full of hangers, clothes dangling.

“Daddy! Don’t go!” Melissa cried as he stomped out the front door.

I followed him. “What are you doing?”

“Leaving,” he said, throwing clothes on the car seat. “And you’re not taking my kids out of school.”

“Really? They’re my kids too!” I screamed, running behind him as he returned to the house. Rummaging in the closet, he threw more clothes on the bed.

“Please don’t leave like this!” I whimpered. I hated clinging but believed I couldn’t survive without him. In our thirteen-year marriage, he’d never threatened to leave. I’d thought of leaving myself—many times, but never had a real job or enough money. “Wives should be kept barefoot, pregnant and, in the kitchen,” he often said joking, but it wasn’t a joke.

“Besides, you’re drunk,” I said. “You can’t drive.”

“I’m sick of being nagged to death about my drinking!”

“Well then, why don’t you stop?”

He leaned inside the closet. I grabbed his car keys off the dresser. He lunged at me. I jumped back. He grabbed my shoulders. Breathing stale beer in my face, he pushed me against the wall. Keys clutched in my fist, I wriggled free, dashed out the front door, and ran across the lawn, Stuart chasing me, I threw his keys into the planter overgrown with ivy.

Like an innocent child playing a game of Freeze, he froze in the dark. His feet stuck in the grass, eyes squinted, he gripped the top of his head in a sobering gesture of disbelief. Feeling no victory in winning the battle, I went back inside. The kids wandered into the street to get a better view of the inferno in the foothills behind Royal Oaks School. Fire trucks raced by sirens blaring. I set Stuart’s warmed-up steak on the table and made my bed on the couch.

Terry took a flashlight out of the kitchen cupboard. “We’re going to help Dad find his keys in the ivy.” My son, now thirteen and taller than me, put his arm around my shoulder. “Don’t worry, Mom, Dad will quit drinking someday.”

I didn’t want him to feel responsible for me. He was still a child. I regretted burdening him with my obsession to make Stuart stop drinking–so we could have a normal family.

Our lives were as out of control as the conflagration moving down the mountain toward our home, days once filled with magic, now turned to mayhem. Our family, like Terry’s magic rope the little girl cut in half, needed a magician with the power to change the trajectory of our lives and restore us to wholeness.

![]()